The history of climatism, Part 4

Saving billions

“The environment matters. So do property rights, trade, development, agriculture, medicine, energy, the rule of law, democracy, and the uncountable other constituent elements of human flourishing. A reasonable environmental policy can work with that, but a spiritualized and cultic environmental policy cannot.”

—Kevin D. Williamson (b. 1972), American political commentator (i)

Part 3 of this timeline on climatism ended with Karl Marx thinking communism was a good idea in 1848 and his mother hoping her son should be thinking about making money rather than just writing about it.

1850

Frédéric Bastiat (1801-50), the French economist, wrote What is Seen and What is Not Seen, an early discussion of opportunity costs. He points out that policies often focus on the seen benefits but omit the unseen costs or risks.

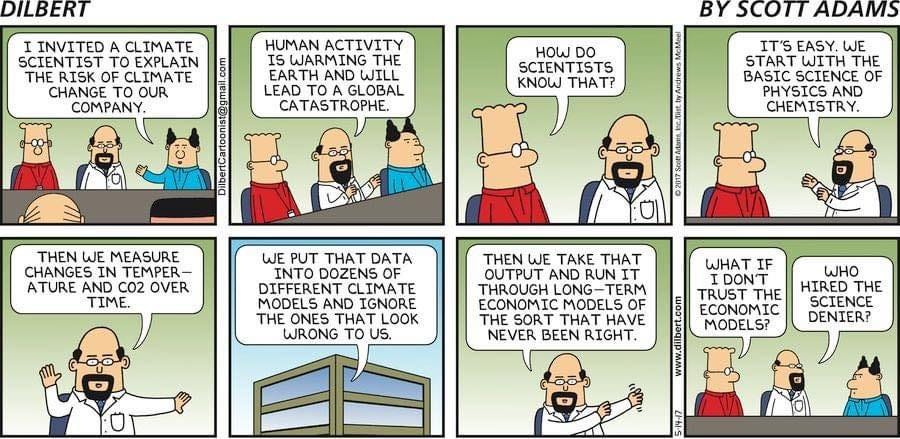

This is quite relevant to the present day when environmentalists suggest banning this or that, i.e.; they want to reverse or halt progress in the name of the precautionary principle or a misanthropic ideology. A pesticide ban, for example, reduces the seen risk of robins dying but elevates the unseen risk of humans dying from the intervention. More on this in parts 6 and 7.

“The bad economist pursues a small present good, which will be followed by a great evil to come, while the true economist pursues a great good to come, at the risk of a small present evil.”

—Frédéric Bastiat[1]

Today, we might just call it a marketing or PR trick: emphasise the policy's benefit and omit or downplay the risk or cost. The benefit, the good intentions, is what gets people elected or guarantees continued research funding. The costs, risks, or side effects cause misery, i.e., get humans killed in some interventionist cases.

“The welfare of the people in particular has always been the alibi of tyrants, and it provides the further advantage of giving the servants of tyranny a good conscience.”

—Albert Camus (1913-60), French philosopher [13]

1856

Eunice Foote (1819-88), the American scientist, conducted experiments demonstrating the greenhouse effect, i.e., how certain atmospheric gases trap heat from the sun.

1859

Edwin Drake (1819-80), the American businessman, struck oil in Pennsylvania, thus starting the first oil boom. A couple of decades later, the modern fossil fuel-burning internal combustion engine car was invented, perhaps the most important consumer product of the Industrial Revolution.

“The more subsidies you have, the less self-reliant people will be.”

—Lao Tzu (around 6th – 4th century BC), Chinese philosopher [2]

Someone once claimed that humankind has never run out of something useful. Based on this argument, something useful will rise in price until it is replaced with something cheaper and/or more efficient. While doomsters and zoophilists might have sounded the alarm bells about humanity running out of whale oil one hundred years ago, we didn’t. We replaced it with something even more efficient: crude oil. And so on. Crude oil will be replaced by something else long before it runs out.

“Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government program.”

—Milton Friedman (1912-2006), American economist [3]

One of the more reasonable ideas of environmentalists is to stop subsidising fossil energy. The price for gasoline, for example, is everything but a free market price. The yellow vests in France are not the only ones that appreciate low gasoline prices; Americans like them, too. One somewhat comical aspect about subsidies, or governmental goodies in general, is that once introduced, it is political suicide to try and remove them. It’s best not to intervene in the first place.

1863

John Tyndall (1820-93), the Irish physicist, explained the “greenhouse effect” in a public lecture and found that water vapour is the strongest absorber of radiant heat in the atmosphere and is the principal gas controlling air temperature.

1864

George Marsh (1801-82), the American diplomat, philologist, and occasionally referred to as the father of American ecology, published Man and Nature, denouncing the depletion of resources, the disfigurement of the countryside, and the harmful role of private corporations.[4]

Spain went to war against former colonies Chile, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru over bird poop, i.e., guano-laden islands in the Pacific. Guano is the accumulated excrement of birds and bats, a highly effective fertilizer due to its high nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium content. Guano has been used as a fertilizer for 1,500 to 5,000 years. While the West discovered its usefulness in the 16th century, Guano became a tradable commodity in the 19th century. According to one source, it traded up to $76 for a pound of it, or four pounds of guano for one pound of gold at the time. (With gold at $2,300 per ounce in April 2024, guano was around $9,200 per pound in today’s hard money terms.)

Excursion: Agricultural revolutions

The Neolithic Revolution, or the First Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period from a lifestyle of hunting and gathering to one of agriculture and settlement, making an increasingly large population possible. This occurred 10,000 years ago in what we today call the Middle East, with some putting the start date 5,000 years earlier in the northern reaches of mainland Southeast Asia.

The Scientific Revolution was a pretty big deal, especially for Europeans. The Scientific Revolution resulted in Europeans having better weapons than everyone else. This means the Europeans shaped the world according to their gusto. Today, apart from societies that stuck to hunter-gatherer lifestyles, the world is “Western,” i.e., everyone wants the Five Cs (cash, car, credit card, condominium, and country club membership), even if the Pope, Jeremy Corbin and AOC say otherwise. (AOC likes the five Cs too.)

Secularisation required the Enlightenment, also known as the Age of Reason, which required the Scientific Revolution. The Industrial Revolution that followed was not only a quantum leap from a productivity perspective but also allowed Europeans to replace slaves with machines that were stronger and more energy-efficient. The Europeans eventually ended slavery during the Industrial Revolution. (It was made illegal by the British on 1 May 1807, to be more precise, after hardly anyone else questioned the morality of slavery for 5,000-9,000 years.[5])

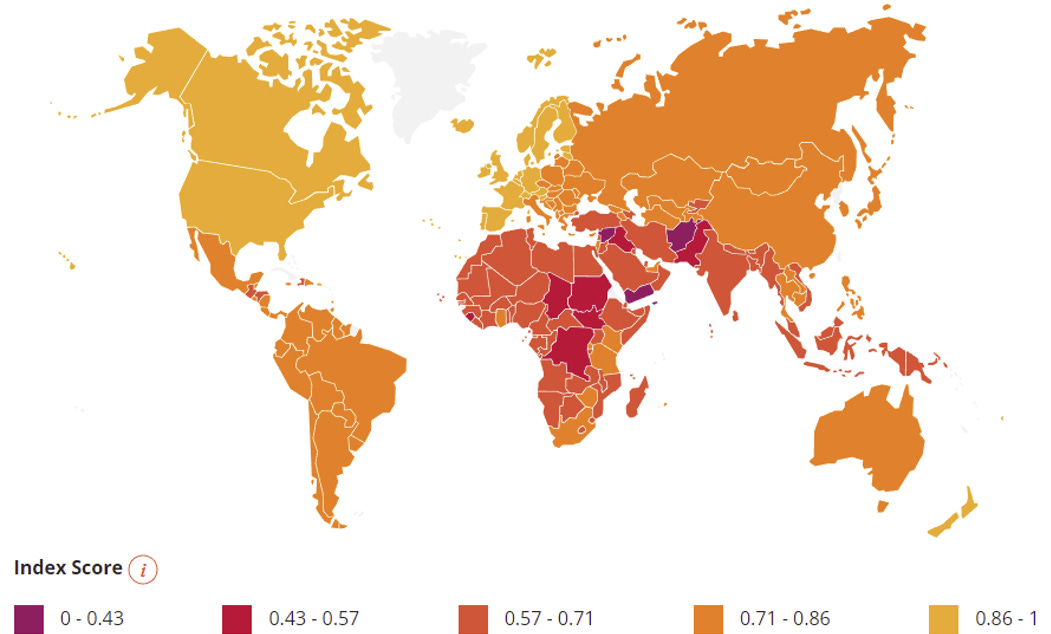

The rise of women's rights was also a function of the scientific-enlightenment-secularisation sequence, a trend far from over. Only in North America and northern Europe do women do well on the Women Peace and Security Index (WPS) mapped below. Most of the planet still has a macho culture, having missed large parts of the enlightenment-secularisation sequence.

The Second Agriculture Revolution, also known as the British Agriculture Revolution, occurred during the Industrial Revolution. One key aspect of this revolution is private property, i.e., the Enclosure Movement. The Enclosure Movement was a push in the 18th and 19th centuries to take land that had formerly been owned in common by all members of a village, or at least available to the public for grazing animals and growing food, and change it to privately owned land, usually with walls, fences, or hedges around it. This is what all the socialists and communists in the 20th century got wrong: ownership capitalism. If you own the land (or anything else), you care. If you don’t, you don’t. No one washes a rental car.

“The reason why slavery is immoral, or rape or murder is immoral, is because it violates private property. And so, if you start with the idea of self-ownership then you can say what is moral and what is immoral.”

—Walter Edward Williams (1936-2020), American economist [14]

One socialist exception was Deng Xiaoping in 1980. He kick-started the reforms that the British did during the Second Agricultural Revolution, whereas the socialists in India didn’t. This gave China a productivity boost, unprecedented in modern history, and brought all the benefits, the main one being a reduction of human misery. In 1980, China was richer than India on a per capita basis by 1.3x. By 2022, it was 2.5x based on the Maddison database.[6]

Only one key insight made all the difference between China’s ascent and India’s relative stagnation: private property. (Today, India beats China in property rights, as per insert in the exhibit above. One of the few indicators where India does better than China. Economic freedom is another one, of course. Modi’s whip is not quite as tight as Xi’s.)

Crop rotation started during the Second Agricultural Revolution, and efficiency improved. This resulted in growth in everything, i.e., population, prosperity, globalisation, markets, technology, and ideas; essentially, growth in the Five Bs (bucks, businesses, blueprints, bodies, and brains). The growth in ideas, for which blueprints and patents are proxies, was important.

“Without trade, innovation just does not happen. Exchange is to technology as sex is to evolution. It stimulates novelty.”

—Matt Ridley (b. 1958), British banker, journalist, politician and author [7]

The Green Revolution, also known as the Third Agriculture Revolution, was the next quantum leap for providing energy for humans, i.e., food. The two key practices that started the revolution were introducing new and better-yield seeds due to the early start of genetic engineering and the increased use of chemical fertilizers. The bottom line of the Green Revolution is that there is enough food for the entire world population, currently around 2,900 kilocalories (kcal) per person per day, up from around 2,300 kcal in the mid-1960s. Like all revolutions involving reason and science, the basic idea is to produce more with less.

The Green Revolution, it goes without saying, is anathema to environmentalists and deep-ecologists trying to reduce population. To environmentalists, Norman Borlaug, a hero to this author, had this to say:

“Some of the environmental lobbyists of the western nations are the salt of the earth, but many of them are elitists. They have never experienced the physical sensation of hunger. They do their lobbying from comfortable office suites in Washington or Brussels. If they lived just one month amid the misery of the developing world, as I have for fifty years, they would be crying out for tractors, and fertilizer, and irrigation canals, and be outraged that fashionable elitists back home were trying to deny them these things.”

—Norman Borlaug (1914-2009), American agronomist [8]

The Green Revolution is tied to Norman Borlaug, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970. Thanks to him, India, Pakistan, and Mexico went from wheat importers to wheat exporters. According to at least one estimate, he and the Green Revolution saved more than one billion human lives. To humanists, he is a hero. To environmentalists, he isn’t. (Too much irrigation is one argument brought against his work.)

The Fourth Agriculture Revolution is happening now. It includes genetically modified foods, vertical farming, robotics, and AI (artificial intelligence). One example is a robot that, with the help of AI, shoots 1,500 weeds per minute with a laser.

New technologies, particularly the use of AI, allow us to make smarter planning decisions and power autonomous robots. Such intelligent machines could be used to grow and pick crops, weed, milk livestock, and distribute agrochemicals via drone. The advancement in genomics allows us to modify nature even further. In the Green Revolution, genetic modification made seeds more robust, so plants grow in harsher climates. The next step is creating new species.

Some religious people don’t like this fourth revolution because it is akin to playing God, and most many environmentalists don’t like it because it means even more food growth for humanity. (The environmentalist movement is also called the degrowth movement.) The controversy surrounding genetically modified crops (created by inserting DNA from other organisms) provides a frank reminder that there is no guarantee that the public will embrace new technologies. The public might reject it as it did nuclear energy over the past 40-50 years. The rejection of modern farming is to food shortages, as the rejection of nuclear energy is to energy shortages.

1865

William Stanley Jevons (1835-82), the English economist and logician, observed that technological improvements that increased the efficiency of coal use led to increased consumption. The Jevons paradox occurs when technological progress or government policy increases the efficiency with which a resource is used, but the rate of consumption of that resource rises due to increasing demand.[9]

If pro and con are opposites, wouldn't the opposite of progress be congress?

Today, LED lighting is a good example. Satellite night images of cities pre- and post-LED show a big difference, i.e., cities are much brighter today. Some call it light pollution, others progress.

1866

Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919), the German zoologist, naturalist, eugenicist, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biologist and artist, coined the term ecology. Haeckel sought a way to describe the relationships between organisms and their environment, both living (biotic) and non-living (abiotic). The word itself comes from the Greek "oikos", meaning "house" or "place to live," reflecting the idea of ecology as the study of organisms in their homes.

Haeckel held views on race, nationalism, and eugenics that resonated with some early Nazi ideology. He believed in Nordic superiority and supported racial hygiene. The Nazis cherry-picked quotes and ideas from Haeckel to justify their racist and nationalistic agenda. They ignored aspects that conflicted with their views. However, Haeckel wasn't a perfect fit for the Nazis. He rejected anti-semitism.

1892

John Muir (1838-1914), the Scottish-born American preservationist known as "John of the Mountains" and "Father of the National Parks," founded the Sierra Club. The club was one of the world's first large-scale environmental preservation organisations and is known for lobbying mostly liberal and progressive politicians to promote environmentalist policies. The club is an early indication that environmentalism and social change are interlinked. The club's recent focus has included promoting sustainable energy, mitigating global warming, and opposing the use of coal.

1890-1940 Average surface air temperatures increase by about 0.25°C.

1940-1970 Average surface air temperatures decrease by about 0.2°C.

1895

Climate experts feared global cooling in the late 1880s, as The Times put it on 24 February 1885: “Geologists Think the World May Be Frozen Up Again.” Those concerns lasted well into the late 1920s. But when the earth’s surface warmed less than half a degree, newspapers and magazines responded with stories about the new threat: global warming. By 1954, Fortune magazine was warming to another cooling trend and ran an article titled “Climate – the Heat May Be Off.” In the 1970s, it was an imminent ice age that was the main threat. Time Magazine on 24 June 1974: “Climatological Cassandras are becoming increasingly apprehensive, for the weather aberrations they are studying may be the harbinger of another ice age.” Then, in the 1980s, it was global warming. Again. Currently, it is “climate change”. At the time of writing, that is. The variation of expert opinions seems much more volatile than the climate itself.

Falling temperatures for multiple decades, while CO2 levels rose strongly during the post-WWII economic boom, do not fit the IPCC narrative of recent years very well.

1896

Svante Arrhenius (1859-1927), the Swedish founder of physical chemistry, became the first to quantify carbon dioxide’s role in keeping the planet warm positively, potentially preventing the next ice age. He later concluded that burning coal could cause a “noticeable increase” in carbon levels over centuries. [10]

“By the influence of the increasing percentage of carbonic acid in the atmosphere, we may hope to enjoy ages with more equable and better climates.”

—Svante Arrhenius

1900

Knut Angstrom (1857-1910), the Swedish physicist, discovered that even at tiny atmospheric concentrations, CO2 strongly absorbs parts of the infrared spectrum, thus showing that a trace gas can produce greenhouse warming.[11]

1904

Fritz Haber (1868-1934), the German chemist, joined the list of scientists who tried to synthesise guano. By 1909, Haber synthesised ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen. This invention, which resulted in a Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918, was important for the large-scale production of artificial fertilisers and explosives.

Haber is also considered the "father of chemical warfare" for his years of pioneering work developing and weaponizing chlorine and other poisonous gases during World War I. His work was also central to Zyklon B, a gas used in the Holocaust ten years after Haber’s death.

Today, it is argued that Haber killed millions (warfare) and saved billions (food production). Around 50% of nitrogen atoms in your body are related to Haber’s invention.[12]

To be continued…

(i) Kevin D. Williamson, Inside the Carbon Cult, 7 April 2023.

[1] Frédéric Bastiat, That which is seen and that which is not seen (Ce qu'on voit et ce qu'on ne voit pas, 1850).

[2] Tao Te Ching, translated by Stephen Mitchell (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 57.

[3] Interview with Phil Donahue in 1979.

[4] Drieu Godfredi, The Green Reich – Global Warming to the Green Tyranny (Texquis, 2019), 17.

[5] Thomas Sowell, Black Rednecks and White Liberals (New York: Encounter Books, 2006).

[6] In 1950 both China and India were equally poor. China increased GDP per capita by 24.1x to 2022, India only by 7.8x.

[7] Ridley, Matt (2011) “The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves,” New York: HarperCollins.

[8] Gregg Easterbrook, “Forgotten Benefactor of Humanity,” The Atlantic, January 1997.

[9] From Wikipedia, 25 May 2021.

[10] Timeline: How the world discovered global warming, reuters.com, 2 December 2011.

[11] Richard Black, “A brief history of climate change,” BBC, 20 September 2013.

[12] Veritasium, 22 July 2022

[13] Albert Camus, Resistance, Rebellion, and Death (New York: Knopf, 1960), originally a speech delivered 7 December 1955 at a banquet in honour of President Eduardo Santos, editor of El Tiempo, driven out of Colombia by the dictatorship.

[14] Walter Williams, Suffer No Fools, PBS Biography, 6 September 2014.