The Five Bs, 1/5

Brains and the iron law of capital

“Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat its mistakes.”

—George Santayana (1863-1952), Spanish-American philosopher1

This is a new series on the Five Bs (brains, bodies, bucks, businesses, and blueprints). Getting the Five Bs wrong means societal decline.

Brains and the iron law of capital

Brains are part of a society’s capital. Getting the Five Bs (brains, etc.) wrong means misallocating capital. Misallocating capital means waste, i.e., inefficient use of scarce resources. Inefficiency means less investment. Less investment means lower growth, or, to use a newer word in left-wing propaganda economics, degrowth. Degrowth means societal decline. Fortunately, there is the iron law of capital for civilised societies empowered by reasonable people.

My favourite definition of the iron law of capital, sometimes referred to as Wriston’s law of capital, is named after Walter Bigelow Wriston. Walter Wriston was a banker and former chairman and CEO of Citicorp. As chief executive of Citibank/Citicorp (later Citigroup) from 1967 to 1984, Wriston, according to economist Henry Kaufman, was “the most influential banker of his day, and probably since.”2 The term “Wriston’s law of capital” was coined by publisher Rich Karlgaard from Forbes magazine in an article on his blog, Digital Rules, in 2006:

“Capital will always go where it’s welcome and stay where it’s well treated…Capital is not just money. It’s also talent and ideas. They, too, will go where they’re welcome and stay where they are well treated.”

—Walter Bigelow Wriston (1919–2005), American banker3

The key is that capital is not just money; it’s people and ideas too. I believe that the iron law of capital has some predictive power. It allows us to identify trends in real-time. It allows the identification of economic policy folly. Rational analysts were making fun of Chávez long before Venezuela went Cuba. However, learning from past economic folly is not for everyone:

“I suppose some people would judge that, on balance, Mao did more good than harm.”

—Diane Abbott (b. 1953), British Labour Party politician4

The Communist Manifesto was written in 1848. History has taught some of us a lot since then. If you replace the word “chains” with “brains,” the quotation below is reasonably consistent with the iron law of capital and capital flight today.

“Workers of the world unite, you have nothing to lose but your chains.”

—Karl Marx (1818–83), German revolutionary socialist5

Chains and brains

The most prominent contemporary example of welcoming capital in a broader Five Bs sense is the United States of America. For most of its short history, the US has been a magnet for capital, i.e., risk capital, people who want to work hard, people who want to study hard, people who are unwelcome elsewhere, patents, ideas, talent, blueprints for big bombs, etc. It is no coincidence that Silicon Valley is in the United States. (Neither is it a coincidence that Crypto Valley is in Zug, Switzerland.) Some (European) leaders, to this day, are still disillusioned as to how brain drain works:

One of the most positive, history-changing events I can think of is the Manhattan Project. The Manhattan Project did not just occur randomly in the US. The people behind it left Europe, mainly Germany, for the US, and they took their brains with them.

Imagine how the twentieth century could have evolved if Germany had not been a Semitic anti-magnet but, like the US, a magnet. The brains would have stayed. Little Boy wouldn’t have been called Little Boy and it would have gone off elsewhere, and London’s current architecture would be, how shall I put this, newer. Jim Rogers, who once told a female interviewer that if she knew how bullish he is on commodities, he would be asked to leave the room, articulated the iron law of capital well:

“Capital never cares whether you’re black, white, Communist, socialist, Christian, or Muslim. All it cares about is its safety and its profit. It goes where the opportunities are.”

—Jim Rogers (b. 1942), American investor6

Here is a 2012 quotation that implies that the then-finance minister of France sort of gets the iron law of capital but then sort of does not:

“France remains an attractive country for investment. We have no intention to make France inhospitable, but we are in a period of crisis. It is logical that the wealthiest should make a contribution.”

—Pierre Moscovici (b. 1957), French politician7

To many, what I in Applied Wisdom, my latest book, call the iron law of capital is simply common sense. Mr. Moscovici understood the hospitability bit. However, he still wants to rip off those with the capital; capital here is broadly defined as money, brains, ideas, etc. The immigration of French people into freer nations is going from one all-time high to the next. (There is also inbound immigration to France, for example, from the Maghreb region or Eastern Europe. The same logic applies, i.e., economic opportunities being a magnet for the by-comparison-oppressed. A French business-savvy engineer sees opportunities in Switzerland while an Algerian vegetable farmer spots them in Marseilles.) Savvy, or shall I say industrious, people tend to leave a sinking ship early, taking their brains with them.

Here is perhaps my all-time favourite quotation:

“Chávez is the best president Colombia has ever had.”

—Colombian homeowner8

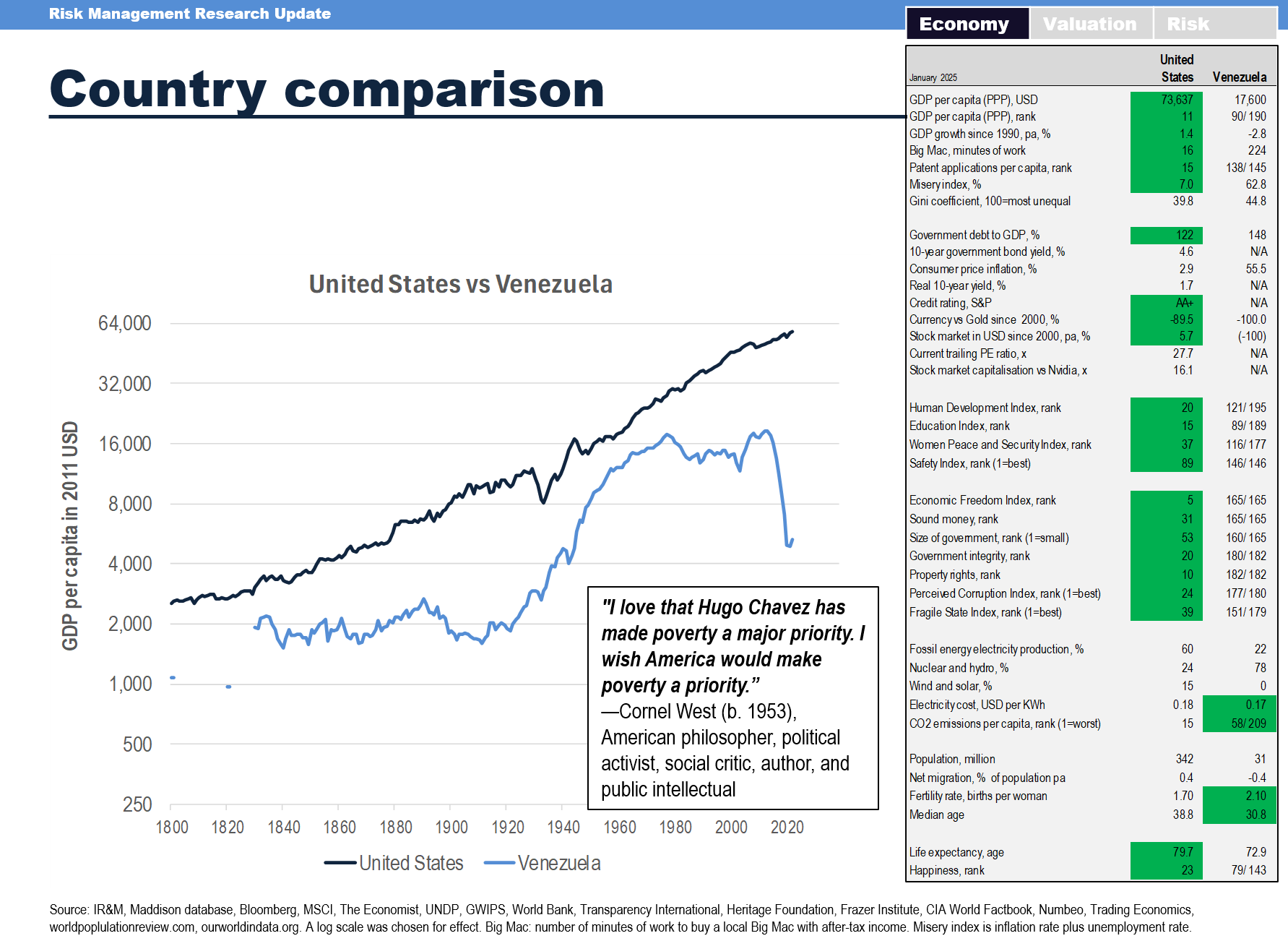

Brain drain is a consequence of systemic issues—such as poor governance, lack of economic freedom, excess bureaucracy, corruption, war, and/or just inefficient institutions—that make it difficult for talented individuals to succeed in their home countries. Brain drain is a big part of the iron law of capital. Below is a comparison between an economy that welcomes the brains and one that drives them away. Venezuela is probably the closest thing to an idiocracy, as millions of brains made their way to Bogota, Miami, and Madrid.

The ideas behind the iron law of capital are ancient. The following text is from the 1520s, an early defence of the non-paternalistic approach:

“Christendom (or shall we say the whole world?) is rich because of business. The more business a country does, the more prosperous are its people…. Where there are many merchants, there is plenty of work…. It is impossible to limit the size of the companies…. The bigger and more numerous they are, the better for everybody. If a merchant is not perfectly free to do business in Germany, he will go elsewhere, to Germany’s loss…. If he cannot do business above a certain amount, what is he to do with his surplus money?… It would be well to let the merchant alone, and put no restrictions on his ability or capital. Some people talk of limiting the earning capacity of investments. This would… work great injustice and harm by taking away the livelihood of widows, orphans, and other sufferers… who derive their income from investments in these companies.”

—Augsburg, in the 1520s9

Chávez never understood this, and Venezuela is suffering as Santayana predicted it would. From the perspective of an optimist, Venezuela is currently learning by doing. Argentina has been “learning by doing” for 100 years and only reversed course a year ago. W. Edwards Deming—an authority on quality management who had to implement statistics into manufacturing in Japan first before he became recognized at home—argues that learning is optional:

“Learning is not compulsory…neither is survival.”

—W. Edwards Deming (1900–93), American statistician and author10

Summary:

Paraphrase, George Santayana, The Life of Reason (New York: Scribner, 1905). Original: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. In the first stage of life the mind is frivolous and easily distracted; it misses progress by failing in consecutiveness and persistence. This is the condition of children and barbarians, in whom instinct has learned nothing from experience. In a second stage men are docile to events, plastic to new habits and suggestions, yet able to graft them on original instincts, which they thus bring to fuller satisfaction. This is the plane of manhood and true progress.”

Henry Kaufman, On Money and Markets: A Wall Street Memoir (New York: McGraw Hill, 2000), 263. Kaufman on Wriston: “Walter is a tall and rather lanky man, with an intense bearing and a dry wit. Economically and politically conservative, he had close ties to the Republican political leadership in his day.” That’s not the end of the story. Kaufman and Wriston were opposites in terms of credit creation. Kaufman was the warner, dubbed “Dr. Doom,” while Wriston was pushing credit expansion. Conversation between the two: Wriston: “Is the world coming to an end yet, Henry?” Kaufman: “Not as long as Citicorp has access to the Fed’s discount window.” Walter Wriston on Henry Kaufman: “For Henry Kaufman, a senior officer of Salomon Brothers with a clear view of its trading floor, to deplore the creation of excess credit is like the piano player in the fancy house protesting that he didn’t know what was going on upstairs.” From Kaufman making reference to a 1986 Wall Street Journal article by Walter Wriston titled “Dr. Doom Takes a Dark View of Regulation.”

Rich Karlgaard, “Predicting the Future: Part II,” Forbes Magazine, February 13, 2006. I first came across Walter Wriston in The Gartman Letter. George Soros said something similar to what I herein call Wriston’s law of capital: “Financial capital is an essential ingredient of production, and it will seek to go where it is best rewarded.” From George Soros, The Alchemy of Finance: Reading the Mind of the Market (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2003), 13. First published in 1987 by Simon & Schuster (New York). Many other economists and down-to-earth practitioners have said something similar. Some call it the iron law of capitalism. I have a preference for the Walter Wriston version because it is short and, more importantly, it includes everything related to capital; money, human capital, patents, ideas, business relationships, and everything. The origin of the idea, though, goes much further back than Wriston.

Diane Abbott, This Week [TV Show], BBC, February 21, 2008. This quote is actually not as stupid as it initially sounds. Russian leaders have denounced Stalin, but Chinese leaders, some of which are neo-Maoists, have not denounced Mao. Deng Xiaoping himself ringfenced Mao from the harshest criticism by declaring that his errors were outweighed by “his contribution to the revolution.” Since Mao’s death in 1976, the Chinese Communist Party’s official line on the issue has been that he was “70 per cent right and 30 per cent wrong.” While many Westerners see Mao as a killing machine akin to Hitler and Stalin, many Chinese today do indeed apply the 70:30 formula to Mao. The Great Leap Forward, Mao’s disastrous campaign to accelerate China’s industrialization by relying on manpower over machines, which led to a catastrophic famine that killed almost fifty million people, belongs in the 30 per cent bucket. Improving the status of women in China, improving literacy and education, getting rid of the Japanese, and trying to unite the country all belong in the 70 per cent bucket.

The quotation used here is a political slogan derived from the Communist Manifesto, 1848, but is not in the original. The original last three sentences of the manifesto were: “Die Proletarier haben nichts in ihr zu verlieren als ihre Ketten. Sie haben eine Welt zu gewinnen. Proletarier aller Länder vereinigt Euch!” The last sentence was the battle cry, the end of the 1848 manifesto.

Jim Rogers, Investment Biker: Around the World with Jim Rogers (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2000), 272. First published in 1994 by Beeland Interest (Miami).

Quoted in Hugh Carnegy, “France Vows to Maintain Tax Hit on Rich,” Financial Times, December 30, 2012.

Quoted in Benedict Mander, “Trouble in Venezuela Brings Benefits to Its Neighbour,” Financial Times, May 8, 2012. By 2012, it was the industrious and savvy who left Venezuela, benefiting the new host. However, by 2018, the influx of refugees from Venezuela became a problem for Colombia, not just a windfall.

Will Durant, The Story of Civilization, Volume 6: The Reformation (Norwalk: Easton Press, 1992). First published 1957 with Simon & Schuster (New York). Ellipses in the original. A committee wrote to the major cities of Germany, asking their advice as to whether the monopolies were harmful, and should they be regulated or destroyed. The quotation is from the response of Augsburg.

I herein use an often-cited variant. Original: “Learning is not compulsory; it’s voluntary. Improvement is not compulsory; it’s voluntary. But to survive, we must learn. The penalty for ignorance is that you get beat up. There is no substitute for knowledge.” W. Edwards Deming, “Quality, Productivity, and Competitive Position,” [seminar], Newport Beach, CA (February 24–28, 1986). From Frank Voehl, Deming: The Way We Knew Him (Boca Raton: St. Lucie Press, 1995).